Ibrahim El-Salahi

Ibrahim El-Salahi did not invent abstraction in Sudan. He made it carry history, restraint, and consequence.

- Ibrahim El-Salahi co-founded the Khartoum School, establishing a Sudanese modernism rooted in calligraphy and African visual systems.

- In 1975, he was imprisoned without charge; the drawings he made during detention reshaped his approach to line, structure, and restraint.

- His work bridged African, Islamic, and modernist traditions and entered major institutional collections, including Tate and MoMA.

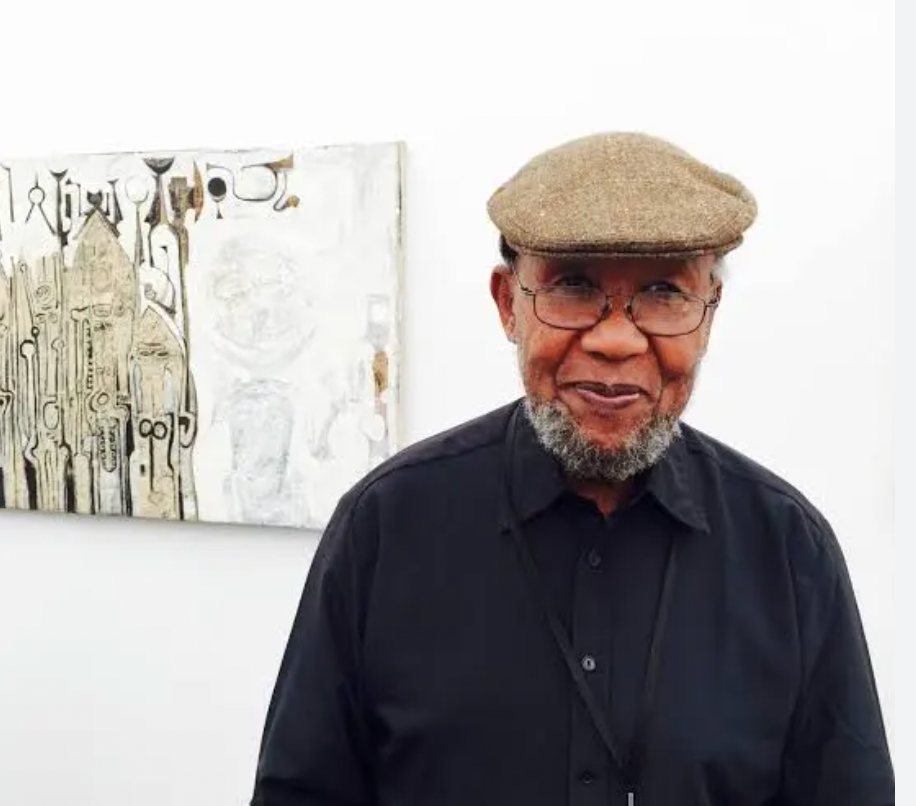

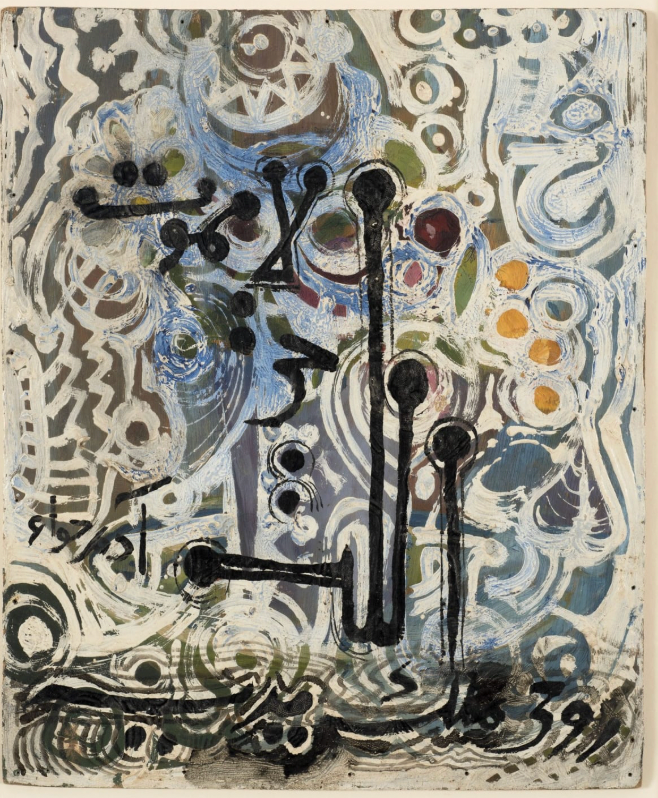

Ibrahim El-Salahi was born in 1930 in Omdurman, Sudan. His first visual education did not come from museums, but from home. His father was a religious scholar and calligrapher, and Arabic script surrounded him from childhood. Letters were not decoration; they were structure, rhythm, and discipline. This early exposure shaped how El-Salahi would later think about form.

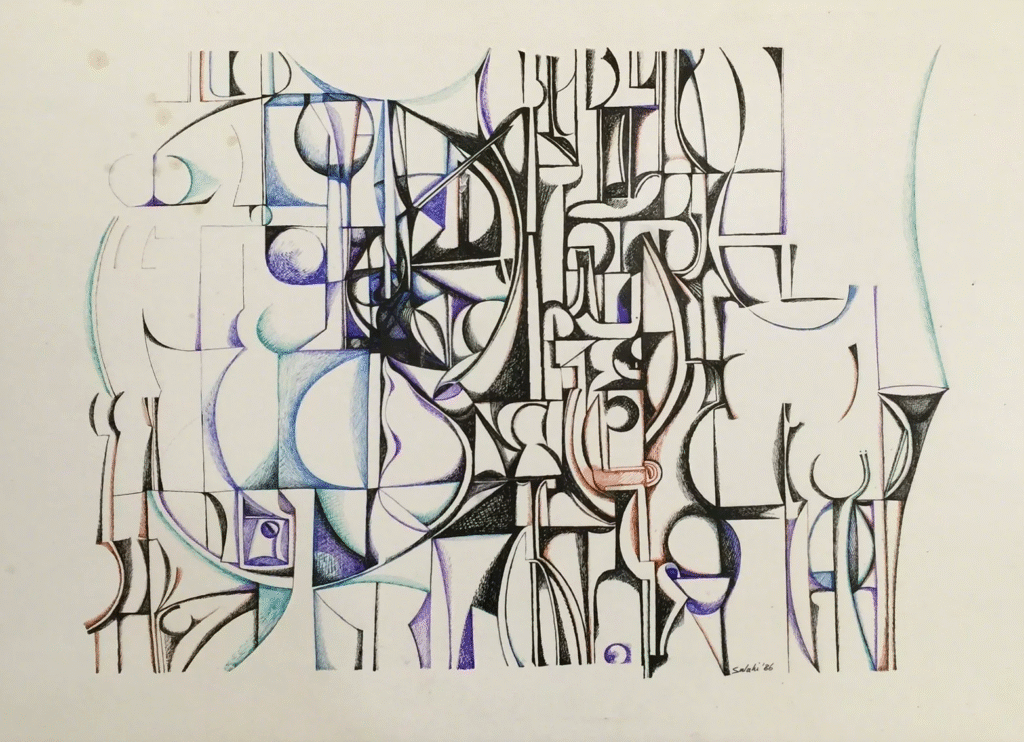

He studied at the Khartoum School of Fine and Applied Art before receiving a scholarship to the Slade School of Fine Art in London in 1954. There, he learned European modernism, Cubism, abstraction, and formal composition.

In the early 1960s, El-Salahi co-founded what became known as the Khartoum School. The goal was not stylistic rebellion, but construction. The group sought a Sudanese modernism built from African, Islamic, and Arabic visual systems.

Alongside his artistic work, he served in public roles, including Director of Sudan’s Department of Culture and later as a cultural attaché in London. In 1975, his life shifted abruptly. He was imprisoned for six months without charge. During this time, he drew secretly on scraps of paper. These prison drawings changed his work permanently. The line became tighter. Forms fractured. Silence entered the page.

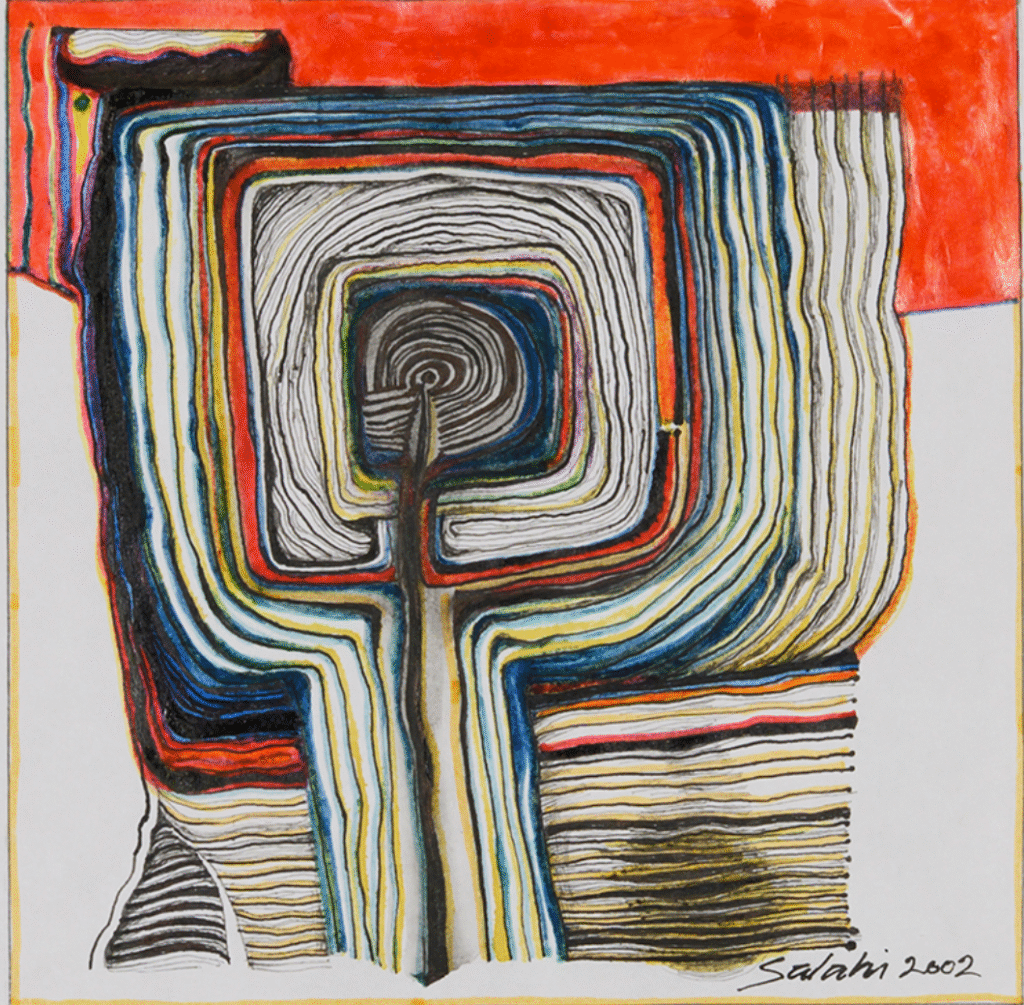

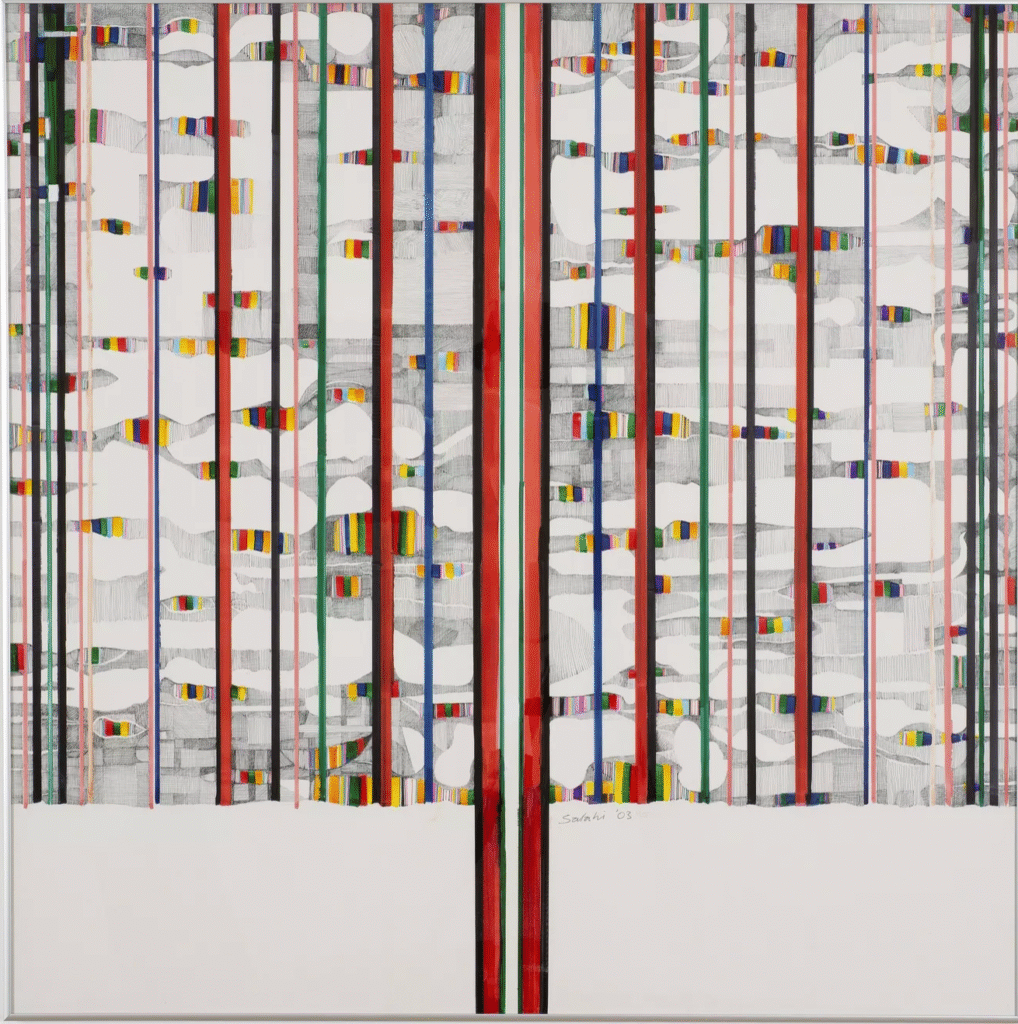

A key example is The Tree (2003). Executed in ink, the composition is built from fine, controlled lines that resemble script but never resolve into words. Branches and roots grow from calligraphic gestures. The tree does not describe nature; it records endurance. It is drawn from the memory of Sudan, of imprisonment, of survival. This is El-Salahi’s mature language: restrained, layered, and precise.

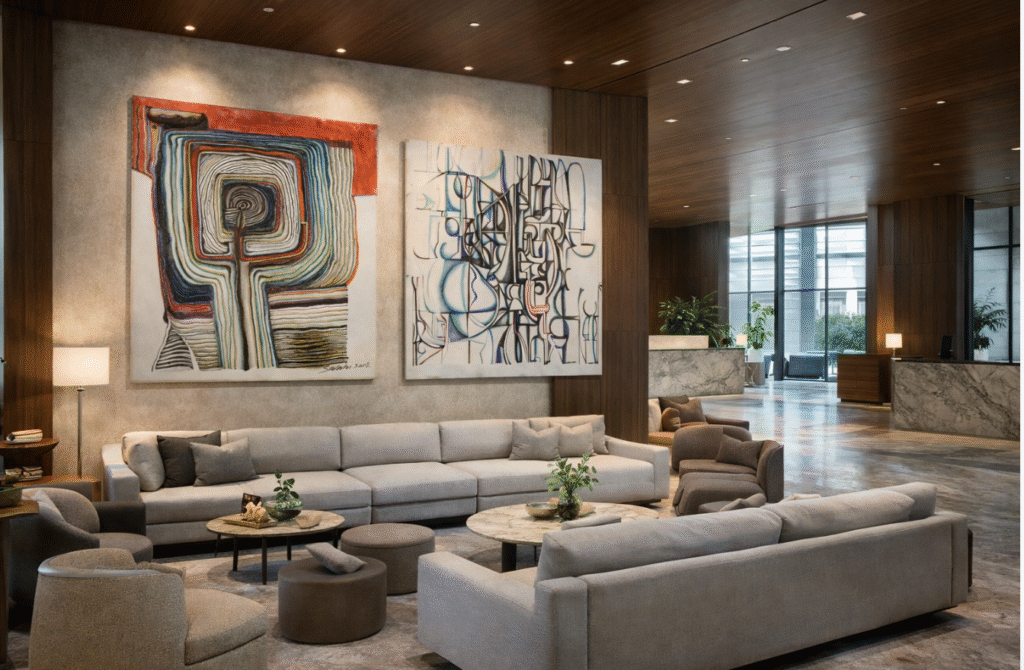

El-Salahi’s work is held in major collections, including Tate Modern, MoMA, the British Museum, and the Art Institute of Chicago. Yet his importance lies less in recognition than in method. He proved that African modernism could be built internally, through structure, memory, and discipline.

Still working well into his nineties, El-Salahi’s career stands as a record of continuity. He did not abandon tradition, nor did he romanticize it. He studied it, broke it down, and rebuilt it. His work shows that modernism is not a destination. It is a process of choosing what to carry forward.

How do u fancy his art on your walls?