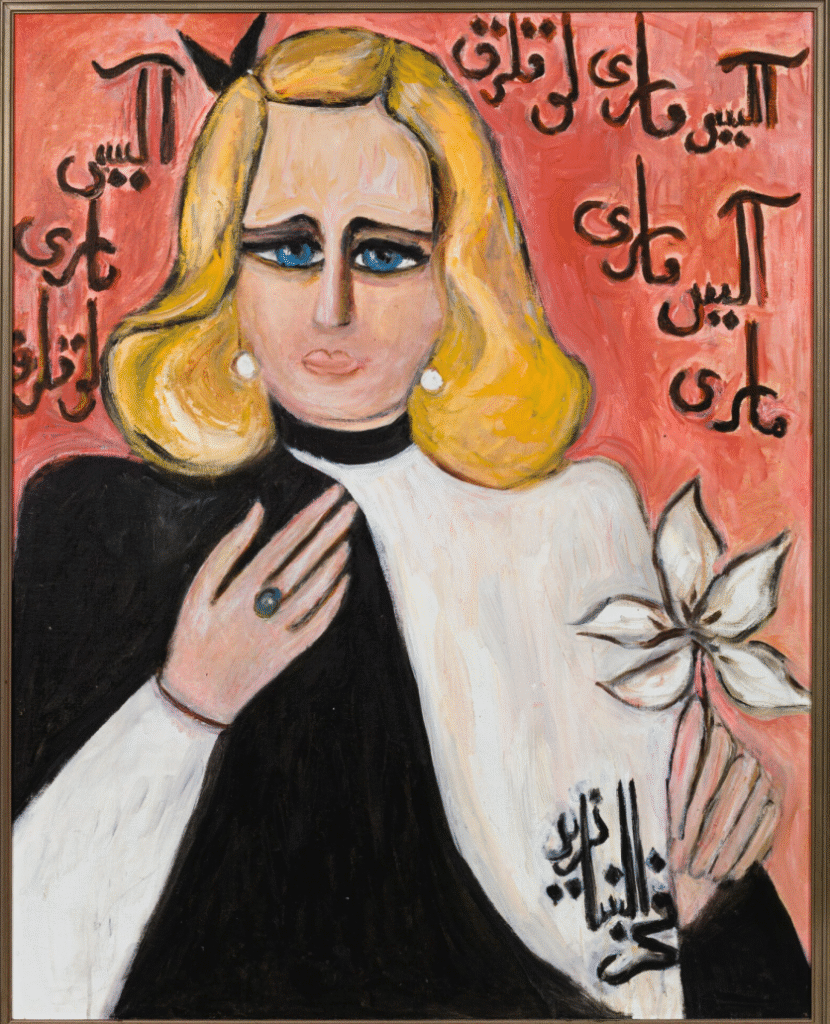

Princess Fahrelnissa Zeid

She merges Ottoman heritage, European modernism, and a life full of displacement and reinvention.

- She built a new abstract language by combining influences from Istanbul, Paris, London, and later Amman.

- She used art to turn personal upheaval into colour and control.

- She shaped Jordan’s emerging contemporary art scene.

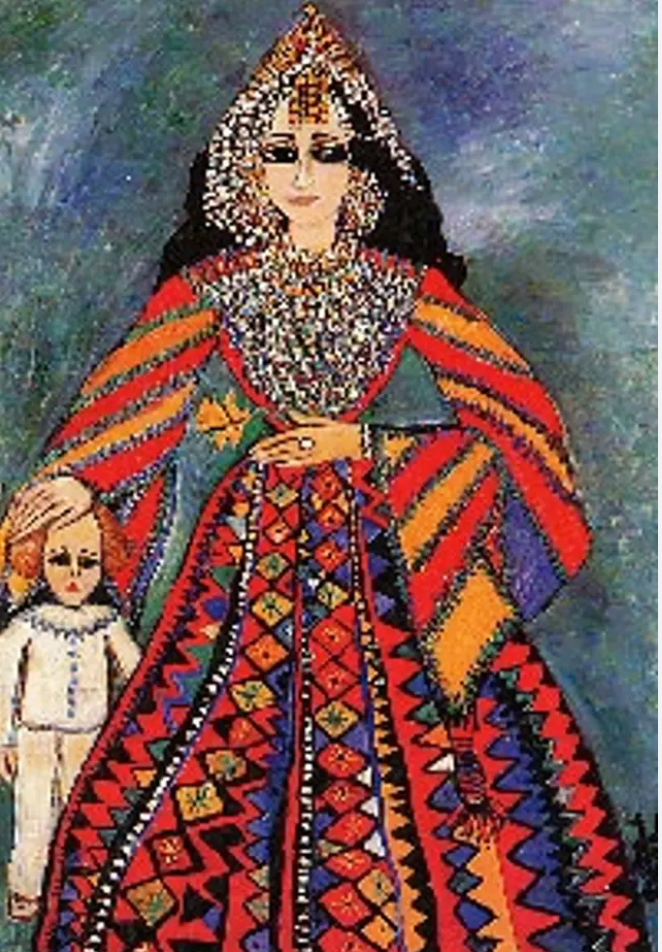

Fahrelnissa Zeid (1901–1991) grew up in an influential Ottoman family in Istanbul and studied at the Academy of Fine Arts for Women. She later continued her training in Paris. These years exposed her to both Ottoman artistic memory and European avant-garde movements, giving her the two foundations she would later merge into her own modernist language!

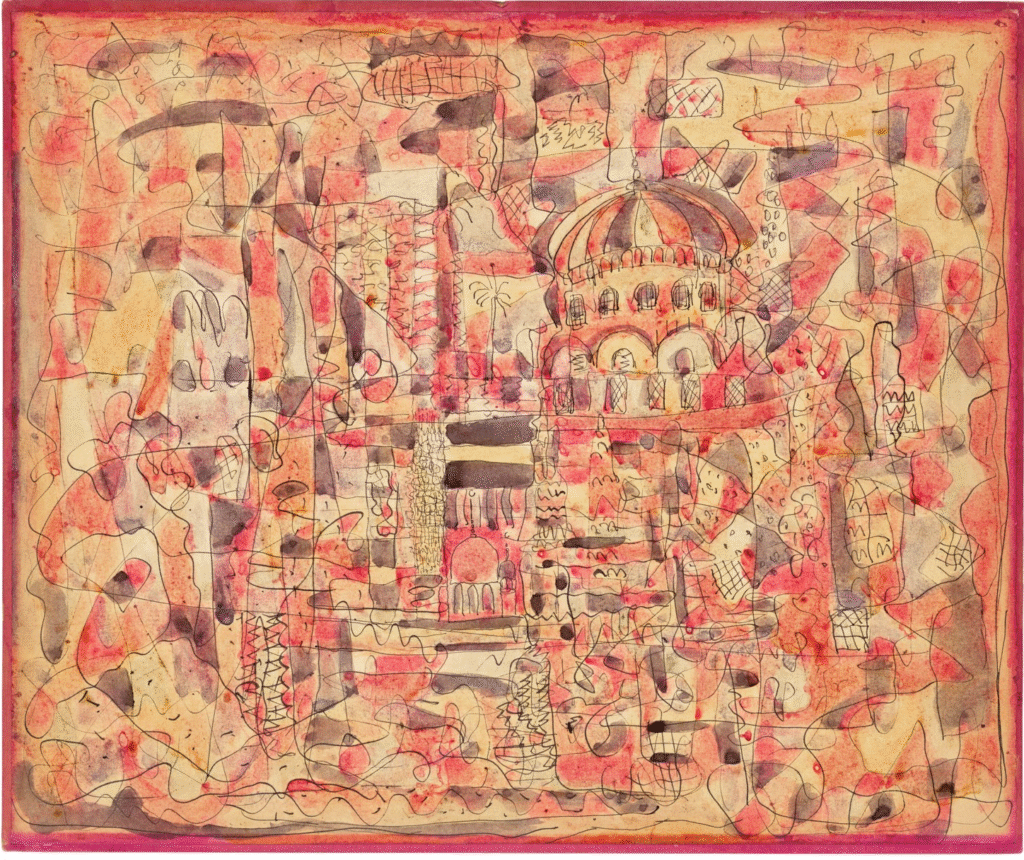

Her life took a diplomatic turn when she married Prince Zeid bin Hussein of Iraq. She lived in Berlin, Baghdad, and London, moving between cities shaped by shifting politics. These changes brought opportunity but also instability. A key turning point arrived in the late 1940s, when political upheaval and personal challenges forced her to rethink her work. She stepped away from representation and committed fully to abstraction.

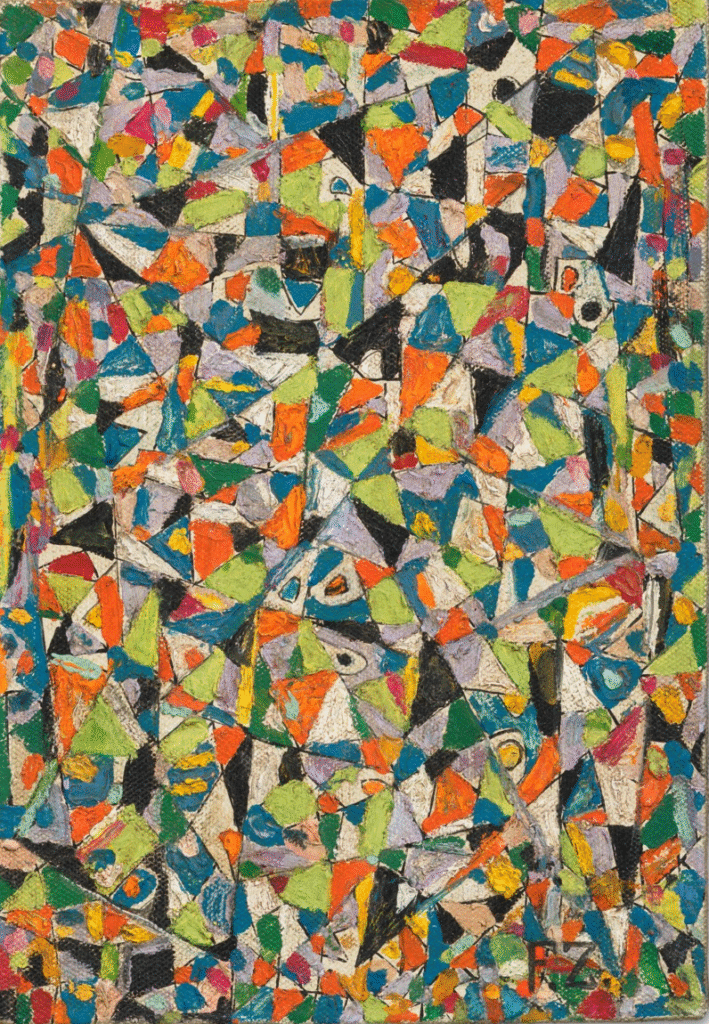

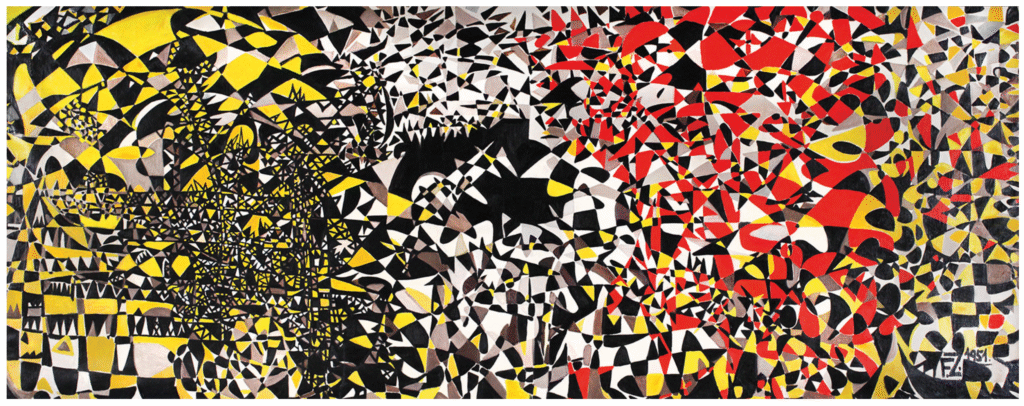

A central example of this shift appears in My Hell (1951).

The painting is built from sharp lines and fractured colour fields arranged in an almost architectural pattern. Nothing is symbolic or descriptive. The viewer meets a controlled system of tension and release, created entirely through geometry and tone. The work matters because it marked her break from figurative art and defined the visual language she used throughout the next decade. It also shows how she handled a crisis: she reorganized it into form.

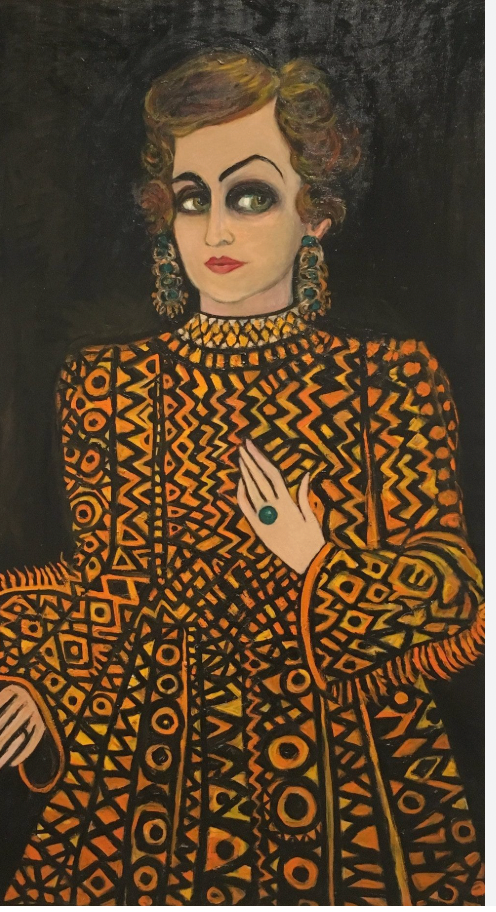

Zeid’s approach sits inside a wider moment in Arab modernism. While many artists in the region used calligraphy or Islamic motifs to claim cultural identity, Zeid took a different path. She created a cosmopolitan abstraction that reflected her movement across cities and cultures. Her paintings connect Ottoman aesthetics, Parisian modernism, and her own experience of displacement. This made her one of the first artists from the region to enter major Western museums, including Tate Modern.

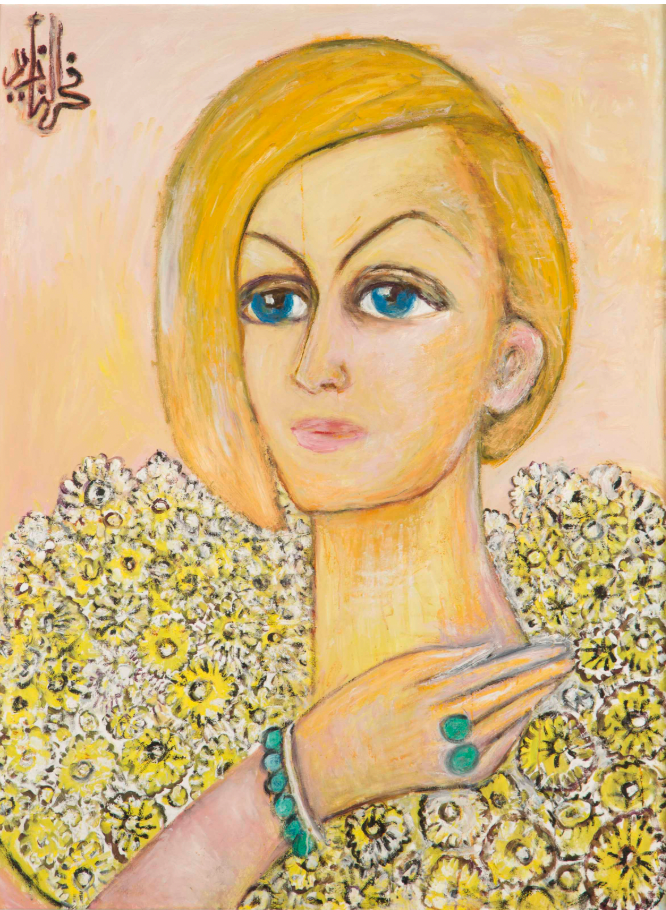

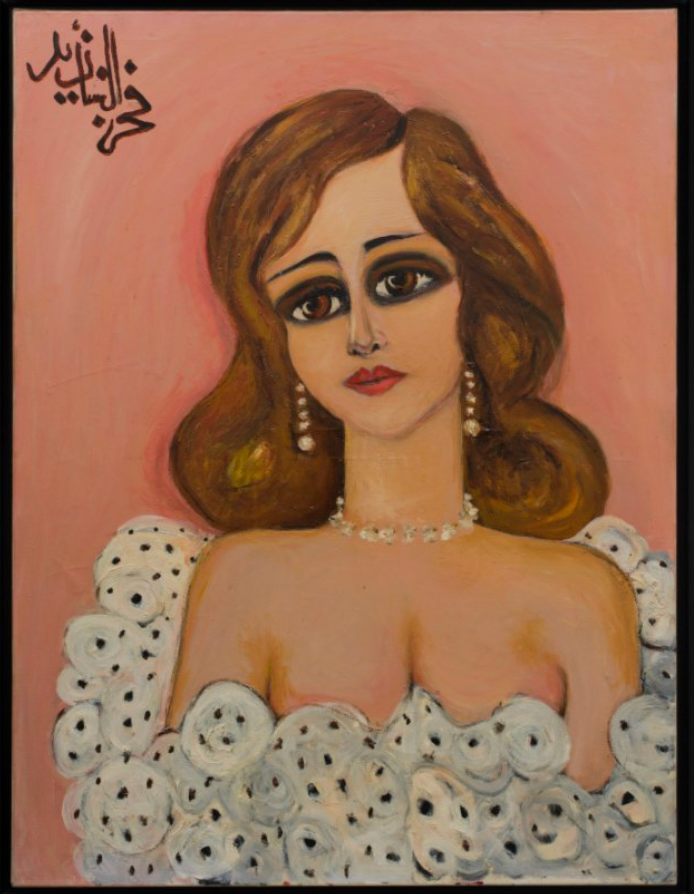

She moved to Amman in the mid-1970s and shifted her practice again. She painted more portraits and created an informal school that trained a new generation of Jordanian women artists. This chapter broadened her role from painter to mentor and made her part of the foundation of contemporary art in Jordan.

Zeid’s legacy matters today because she proved that Arab modernism does not need to choose between heritage and global influence. She built a disciplined visual language that carried both. Her story continues to show how clarity, resilience, and cultural intelligence can shape a lasting artistic identity.